Rubén Blades and His

Cast of Characters

|

This page will try to honor the literary quality of Rubén Blades lyrics by highlighting the characters that live in his songs. Mr. Figueroa's article gives a cultural context for stories in songs, and identifies the familiar types seen in any barrio. Rubén's own words give a further context, taken from various news sources, from Sergio Santana's book Yo Rubén Blades, and an interview by Pete Hamill in 1986 (excerpts reprinted with permission of the author.)

The quotes are in English and Spanish, as I have found them. ~Alison

| RUBEN

BLADES AND HIS CAST OF CHARACTERS Frank M. Figueroa (originally in Latin Beat magazine, reprinted with permission of the author) There is a long tradition in Hispanic culture about telling stories in song. In Spain, during medieval times, the cantares de gesta or geste songs told about the daring adventures of fabled characters. Eventually many of these were collected in Cancioneros or collections of verse. This tradition was brought to America by the Spaniards. In due time, the payadores or minstrels of the pampas in Argentina and the troubadours of other Latin American countries began composing and singing their narrative songs. Much of the tango music of Argentina, the guajira music of Cuba, the plenas of Puerto Rico, and the Mexican corridos and huapangos also grew out of those early roots. These folk ballads of the early troubadours had long lyrics and told complete stories about famous folk heroes and historical events. Frequently, the characters were easily identifiable and at other times they were symbolic figures incorporating traits taken from several real-life individuals. These characters immortalized in song were not always models of virtue. Some of them were bandits, rebels, and fugitives. Invariably, they had a redeeming quality that endeared them to the people. Names such as: Martín Fierro, Agüeybana, Juan Charrasqueado, Pancho Villa, and Hatuey quickly come to mind. In recent times, a composer/singer from Panamá, Rubén Blades, has popularized the narrative salsa. Breaking away from the strictly repetitive lyrics of the modality known as salsa, he chose to tell complete stories in his songs. Empowered by a good education and an inquiring mind, Blades set out to write songs that made a difference. He is convinced that you can respect your conscience and the clave rhythm in the same song. He was born and brought up in the middle-class neighborhoods of Panamá. In a small country such as his native country, one is never too far removed from the slums. In fact, it is not rare to find ramshackle homes next to mansions in the city. Rubén, therefore, internalized early in his life the sorrows, frustrations, and dreams of the poor and destitute in his country. Blades despised the attitude of the rich toward the poor that glossed over their miserable living conditions by saying: "They are used to living that way." He had come face to face with the picaresque characters that marauded the streets of the barrio. These encounters left an indelible mark in his memory. The writings of Franz Kafka, Gabriel García Márquez, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, as well as existentialist and tremendista authors provided him with more raw material for his songs.  Speaking

about the entities in his songs, Blades says: "That entire series of

characters are exactly the same in all Latin America. I have had

them near me since infancy." In the creation

of his characters, Blades draws from his personal experience. In

addition, he

has the ability to symbolize very profoundly events from outside his

own

experience. The result are characters that truly represent what man has

suffered in Latin America throughout the centuries. The composer

establishes a

strong link with the listener immediately. Those living in the

barrios

anywhere in the Hispanic world need no introduction since they are

personally acquainted with the characters. The rest of us view the

action and

the characters as in a movie or television screen with all the realism

it can

convey and yet, having unreal, weird, and nightmarish overtones.

Speaking

about the entities in his songs, Blades says: "That entire series of

characters are exactly the same in all Latin America. I have had

them near me since infancy." In the creation

of his characters, Blades draws from his personal experience. In

addition, he

has the ability to symbolize very profoundly events from outside his

own

experience. The result are characters that truly represent what man has

suffered in Latin America throughout the centuries. The composer

establishes a

strong link with the listener immediately. Those living in the

barrios

anywhere in the Hispanic world need no introduction since they are

personally acquainted with the characters. The rest of us view the

action and

the characters as in a movie or television screen with all the realism

it can

convey and yet, having unreal, weird, and nightmarish overtones. The cast of characters in his songs include: campesino rebel leaders, barrio bullies, pariahs, prostitutes, parish priests, and plain poor folk. Following the model of the tremendista novels, the characters in Blades' songs are victims of society. Their fate is set at birth and are programed for failure. It is possible, therefore, to view them with some sympathy instead of being repelled by them. Rubén blames society, not God, for man's plight. The God-created paradise he gave us was lost and now we must live in a man-made hell. Perhaps the best portrayed character in the composer's songs is Pedro Navaja [Letras][English] . It is ironic that the last name "Navaja" can be translated into English as "switchblade." Although the setting for this episode is a Puerto Rican ghetto in New York City in the 1960s and 70s, this guapo or matón (bully) is a familiar figure in the barrios anywhere in the Hispanic world. Driven to the streets into a life of crime by an inexorable fate he is like a predator with inborn instincts to prey upon the weak. As such he cruises the streets of the barrio ready to strike at the first sign of weakness of any of his victims. Blades' supplies Pedro Navaja with all the necessary conditions and equipment for the hunt. The environment is the crime-infested streets of a New York barrio where the residents have grown calloused and indifferent to what happens around them. Criminals are free to commit their felonies, protected by the anonymity and indifference of the slums. In addition, the action is set in the darkness of night making detection much more difficult. Pedro Navaja wears a broad-brimmed hat tilted to one side to shield his face, dark glasses, a coat with deep pockets to keep his knife and hands out of sight. For a fast getaway, he is equipped with lightweight shoes and a gold tooth whose gleam sheds light on his path. He cruises the streets and is ready for action, a despicable figure and yet, the way Blades portrays him, we cannot really hate this monster. We surmise that he has no marketable skills to earn an honest living. It is evident that Pedro Navaja is a hold-up man and may even be a pimp. Why didn't he break out of the strangle hold of the barrio and lead a law-abiding life? Perhaps, as the protagonists of the novels of the naturalism period in literature, his parents passed on to him this legacy of crime and violence through their genes. Was it society that denied him the skills and the opportunity to lead a decent life? Was it the ravages of a love betrayal that turned him into a negative being seeking revenge at any cost? We get subtle indications that some of this happened. The woman in the song, who is not even worthy of a name, is called esa mujer (that woman). She is capable of sending him into a wild rage. Was it the final affront of seeing the woman he loved dearly and who betrayed him now turned into a common prostitute? We don't really know, but Pedro Navaja laughs while he stabs her repeatedly and without mercy. Esa mujer shoots Pedro Navaja almost simultaneously and has the last laugh when she manages to say: "I thought this wasn't my day, that I was cursed. But you're worse, your nothing, you're nobody." In an ironic final act of mutual charity, these despondent beings take each other out of their misery. The continuity of the cycle of misery is assured by the drunken bum who comes by, stumbles into the bodies, and picks up the revolver, the knife, two dollars and like in a Kafka novel disappears into an alley. The song ends with a radio news broadcast reporting the crime in the typical monotone of newscasts. Ah, but like the phoenix from Egyptian mythology, Pedro Navaja manages to rise again from his ashes. In a sequel song entitled "Sorpresas" Rubén Blades tells of how the drunken bum who picked up the gun, the money and the knife was eventually robbed by another predator. The victim is forced to give information about the location of the bodies. The robber finds the bodies and is stabbed to death by Pedro Navaja, who apparently had not been mortally wounded. Pedro puts his own identification papers in the back pocket of the robber in order to foil the investigation. He leaves apparently free to continue his miserable life. Another member of Ruben Blades' cast of characters is Juan Pachanga. [Lyrics] The composer takes him from the rogue's gallery of every Hispanic barrio, and gives him a symbolic name. Pachanga means "partying," "a time of drinking and dancing." Juan is the neighborhood's mamito or playboy. As is frequently the case in the urban slums, no one knows him well enough to determine how he makes a living, or where and how he lives. Juan Pachanga is, nevertheless, a very familiar figure in the streets. Everyone who goes by greets him with a "Hey men," but that is the extent of their contact with him. As far as they know, he is a perfectly happy-go-lucky man. They don't know that in his heart he is carrying the severe pain of a betrayed love. We know that Pachanga is a mamito and by definition, he is living off some woman he doesn't really love. Blades' contrasts Juan's strange behavior against that of the other members of the barrio. In the early hours of the morning, while the rest of the community sleeps, Pachanga is still out in the street. He is the consummate pariah. One gets the impression that Ruben Blades is acting as a movie- writer-director when he writes his songs. Before writing his script, he calls Central Casting and gets the character he needs from their large stock of types. The Wardrobe Department supplies him with the appropriate clothing for his character and the Music and Orchestration Division completes the project. Juan Pachanga has been well outfitted by Wardrobe. He wears the most fashionable clothes, colorful well-polished shoes, and gentlemen's cologne. Our character is ready for the cameras and all Ruben has to do is say: Ready, camera, action!  The

composer sees a ray of hope for the people of the barrios. However dim

it may be, it is still there and can

light the way to a better life. It is only fair to say that many

potential

leaders and heroes live in the squalor of the inner cities of the

world. In Pablo Pueblo [Lyrics]

[audio clip English],

Rubén Blades presents us a composite portrait of those

humble hard-working family men who haven't given up in spite of all the

frustrations and failures. These are not the abúlicos (men

who have given up due to a long history of failure) of the Unamuno

novels. The

surname Pueblo is symbolic, as is the case with the two characters

previously

discussed. Pueblo in Spanish means "people" and

that is what he typifies. The composer does not give us a physical

description

of the character. He leaves it for us to fill in the traits and typical

worker's garments he wears, drawing on our own life experiences.

The

composer sees a ray of hope for the people of the barrios. However dim

it may be, it is still there and can

light the way to a better life. It is only fair to say that many

potential

leaders and heroes live in the squalor of the inner cities of the

world. In Pablo Pueblo [Lyrics]

[audio clip English],

Rubén Blades presents us a composite portrait of those

humble hard-working family men who haven't given up in spite of all the

frustrations and failures. These are not the abúlicos (men

who have given up due to a long history of failure) of the Unamuno

novels. The

surname Pueblo is symbolic, as is the case with the two characters

previously

discussed. Pueblo in Spanish means "people" and

that is what he typifies. The composer does not give us a physical

description

of the character. He leaves it for us to fill in the traits and typical

worker's garments he wears, drawing on our own life experiences.

Pablo Pueblo is a silent, tired man whose slow gait betrays his reluctance to go home to face the sad reality of his family life. His reward for a hard day's work is the return to the noisy, garbage filled streets of the slum with its walls filthyfied by the politician's false promises. Pablo Pueblo is condemned by heredity and environment to a life of misery. He is: "the product of the streets and its screams, of misery and hunger, and of the alley way and sorrow. His only sustenance is hope." Those are the words with which Blades describes Pablo Pueblo's condition. In the montuno section of the song, Rubén Blades encourages Pueblo and his counterparts in all Latin America to keep on trying. Following Unamuno's existentialist principles, that man must act, no matter what that action is. Blades urges Pablo Pueblo to pray and have faith in God, try his luck with the horses, the lottery, and even playing dominoes. The important thing is not to be passive. The composer is sympathetic to Pablo Pueblo's plight, he even calls him "Pablito." One gets the feeling nevertheless, that Blades is not sure that Pablo Pueblo will find a solution to his problems. He wants him to keep struggling, to keep hoping and in so doing become "distracted," as Unamuno would say, from the fundamental problems of his existence. The cast of characters in Rubén Blades' songs also include, Ligia Elena [Lyrics], the upper class young girl who falls in love with a poor musician to the chagrin of her parents. In Panamá young girls of this social status were called rabiblancas or white-tailed girls. Rubén's school chum Roberto Cedeño, wrote the first sketch of the lyrics based on a much publicized tryst between a high society lady and a famous Panamanian singer. Blades added the music and finishing touches on the words. The composers used this opportunity to comment on social discrimination in Panamá. They took the name "Ligia Elena" from one of the small tankers used to deliver gasoline to the island of Taboga. In the song Cipriano Armenteros and its sequel Vuelve Cipriano, Blades tells the story of a Panamanian bandit famous in 1806. After being ambushed, he escapes from the authorities and returns later to gain revenge on those who laughed at him when he was a prisoner. Unfortunately, he is captured once again and the song ends with his boast that he escaped once, and will escape again. Other characters of the same mold are: Juan González [audio clip], a famed guerrilla fighter, Carmelo, [Medoro], and Adán García. [Lyrics] The history of personal sacrifice of the Spanish priests who came to America ever since the days of Columbus is recalled in "El Padre Antonio y su monaguillo Andrés." [Lyrics] The song tells the story of the senseless murder of a humble parish priest by a Salvadoran death squad. Padre Antonio gave up his comfortable position at the Vatican and all hopes of becoming Bishop for a dusty, obscure small town in El Salvador. Many of us have known similar Spanish priests serving unselfishly in Latin America. (In fact, at one time some of us assumed all Catholic priests came from Spain.) Padre Antonio left his homeland to come preach the Gospel in shirtsleeves in the sweltering heat of the tropics. In addition to leading souls to Christ, he guided the lives of young men and women such as his altar boy Andrés. Padre Antonio paid the ultimate price for the nonpolitical crime of helping the poor. He and Andrés were murdered during Holy Mass in front of the altar in his parish church. In one of his inspirations in the montuno Blades compares the death of Padre Antonio with the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero by the Salvadoran paramilitary in 1980. While not exactly a cast of thousands, the characters in Rubén Blades' songs are indeed many. You may remember, los Plástico(s) [Lyrics], Manuela [Lyrics], [Paula] C [Lyrics], Rosa Bonilla [?], Madame Kalalú, Juana Mayo [Lyrics/letras] and Doña Lelé. It is possible that in due time, inspired by one of his favorite authors, Gabriel García Márquez, Blades may populate his musical world with as many characters as there are in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Perhaps as in one of Unamuno's novels, the characters in Rubén Blades' songs may even rebel against him and insist on singing their own inspirations in his montunos. Come to think of it, that's a good idea. A song in which the characters sing to their creator, very much like all those tribute albums we have gotten to dislike in recent times. Juan Pachanga improvises a line to which the Coro replies. The others follow suit until none of us, including Rubén, can take it any longer. On second thought, perhaps Rubén Blades wouldn't allow this to happen. His legally trained mind would demand that the order of creation, with the creator on top and his creatures below him, be respected. |

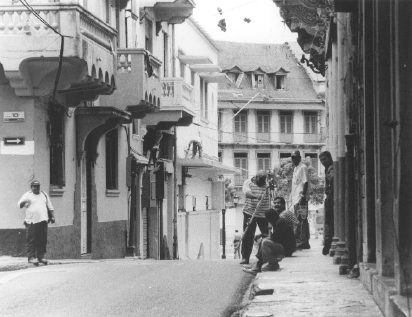

photo by Matt

McCaw

photo by Matt

McCaw

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyrics and audio clips |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"In other words, you gotta be totally clear within yourself about what you're doing and why. The bottom line is that you never know how a song will affect anyone else except you. You just make the statement and hope that it will be understood and that it'll do some good at some point." |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| My thanks to the following

sources: Frank Figueroa - "Rubén Blades and His Cast of Characters" (1997) used with permission Pete Hamill - "It's Rubén's Time" ASCAP In Action (Spring 1986) used with permission Sergio Santana A. Yo, Rubén Blades, Medellin, Colombia Photographer Matt McCaw's Central America Gallery (photos used with permission) News at cronica.com.mx, dailyjournalonlne.com (EFE) Special thanks to Mary Kent, author of Salsa Talks!

|

|||||||||||||

down

this street went

down

this street went  El

cantautor y ministro de Turismo, Rubén Blades, dice

que desde pequeño acostumbra a leer. "La lectura para mí

es una especie

de ejercicio y a la vez un deporte, " asegura.

El

cantautor y ministro de Turismo, Rubén Blades, dice

que desde pequeño acostumbra a leer. "La lectura para mí

es una especie

de ejercicio y a la vez un deporte, " asegura.